The books are not in a ranked

order; instead, they represent a set of texts drawn from a fairly eclectic set

of disciplines. After adding a part II I will try to connect some of the common

themes.

*****************************************************************************

Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers, has been justly praised and awarded for its stirring narrative of slum

living in Mumbai. It took 3 years of her

life to live this world and then some time to craft the prose into something

approaching art. If you have not been to India or you have not watched the documentaries

on how untold millions live, this book will let you in to a world we often do

not wish to admit does indeed exist. We just choose not to see it.

*****************************************************************************

Sam Harris’ Free Will, is

short but quickly devastating to your sense of self. If his thesis is correct,

that humans have no free will, then this book will be remembered in generations

to come, for sounding the death knell to what we thought we knew was ‘human

nature’. A number of well-regarded neuroscientists disagree that the data he

has gathered is conclusive, but it certainly makes a great case for changing

the justice system in the US.

*****************************************************************************

Mortality, by Christopher

Hitchens, not so much for the Vanity Fair articles that have been gathered here,

although they contain the great prose and heroic outlook that made his last

acts anything but a gentle goodnight; instead, this pick is in part for the body of work he

left behind in his many others books and articles. Contrarian, and perhaps the

raconteur supreme of his generation. What most moved me in the book, however,

is the last essay, written by his wife, Carol Blue. It is a devastatingly beautiful summary

of the better angel of Hitchen's nature and should be read by anyone who wants

to learn about love and life.

******************************************************************************

Trust Me, I'm Lying: Confessions of a Media Manipulator, by Ryan

Holiday is problematic in every sense of the word. For some, it might even fall

under the category of evil. This part tell all and part mea culpa is really a

how to book on creating a sensation via social media. The rules are clear and

they are completely amoral. To get ahead, says Holiday, lying and manufacturing

stories is the way to fame and possibly fortune. He gives morally wrong examples that brought him wealth and

fame and only then sort of says he's sorry. But he also sort of gleefully revels in the bad

boy he is. But as a how to book it is undeniably helpful. Whether readers want

to bite this apple of knowledge is a moral question worthy of discussion. And I

have had them with others when working on projects. So far I have not bitten the apple but temptation is tough to resist.

*******************************************************************************

Lionel Asbo State of England, by bad boy Martin Amis, is one I would recommend to be listened to rather than

read. Alex Jennings, the Audible.com narrator captures the demotic poetry of the seamier side of London. Amis has learned and then shared the hard fricatives of Lionel and his nasty, brutish, and short-lived

ilk while somehow making the lout an object d'art while simultaneously demonstrating how his values actually

transcend class once money enters the scene.

Everyman arises. The plot is more of an attempt to teach an object

lesson (in all senses of the term), but the beauty of the words, low and spewed

and twisted, become a lovingly rendered prose poem in the midst of unprovoked

attacks, self-righteous stupidity, and motiveless malevolence. I would also suggest that Amis’ book be

served along with a reading of Theodore Dalrymple’s book, Life at the Bottom: The Worldview That Makes the Underclass (Published in 2003). That book begins by rewriting, with withering wit, Marx’s

opening salvo:

A SPECTRE IS haunting the Western world: the underclass. This underclass is not poor, at least by the standards that have prevailed throughout the great majority of human history. It exists, to a varying degree, in all Western societies. Like every other social class, it has benefited enormously from the vast general increase in wealth of the past hundred years. In certain respects, indeed, it enjoys amenities and comforts that would have made a Roman emperor or an absolute monarch gasp. Nor is it politically oppressed: it fears neither to speak its mind nor the midnight knock on the door. Yet its existence is wretched nonetheless, with a special wretchedness that is peculiarly its own.

Dalrymple is not a sympathetic ear to some of the plights of the poor. Politically correct he is not. And neither is Amis for some quite similar and quite different reasons. In both cases they give a view of the world that exists but is little talked about in either way in polite company.

A SPECTRE IS haunting the Western world: the underclass. This underclass is not poor, at least by the standards that have prevailed throughout the great majority of human history. It exists, to a varying degree, in all Western societies. Like every other social class, it has benefited enormously from the vast general increase in wealth of the past hundred years. In certain respects, indeed, it enjoys amenities and comforts that would have made a Roman emperor or an absolute monarch gasp. Nor is it politically oppressed: it fears neither to speak its mind nor the midnight knock on the door. Yet its existence is wretched nonetheless, with a special wretchedness that is peculiarly its own.

Dalrymple is not a sympathetic ear to some of the plights of the poor. Politically correct he is not. And neither is Amis for some quite similar and quite different reasons. In both cases they give a view of the world that exists but is little talked about in either way in polite company.

*****************************************************************************

Journalism Joe Sacco. This

graphic novel transcends the genre. It is an educational and well-informed book

on war –in the midst of it and also in its repercussions on individuals and

society. It will change your view of what a graphic novel is and make you think

twice about why we thought that visuals like this have not been used to teach

moral lessons and history recently. (The images are starkly drawn and are the

work of an accomplished artist, much as the great work of political satirists

like Hogarth.) The NY Times calls it a “brilliant excruciating book of war

reportage.” It is that and at the same time proof that innovative artists and

thinkers are alive and creating new ways to change our ways of seeing and

thinking.

Journalism Joe Sacco. This

graphic novel transcends the genre. It is an educational and well-informed book

on war –in the midst of it and also in its repercussions on individuals and

society. It will change your view of what a graphic novel is and make you think

twice about why we thought that visuals like this have not been used to teach

moral lessons and history recently. (The images are starkly drawn and are the

work of an accomplished artist, much as the great work of political satirists

like Hogarth.) The NY Times calls it a “brilliant excruciating book of war

reportage.” It is that and at the same time proof that innovative artists and

thinkers are alive and creating new ways to change our ways of seeing and

thinking.

****************************************************************************

|

| Lucretius |

A Universe From Nothing, Lawrence Krauss. I am not quite alone in

seeing the value of the book. Richard Dawkins gives it an afterward and says it

is game changing in its attempt to answer all those who say something cannot

come from nothing. I have talked with a world-renowned astronomist, and he,

like the moral philosopher who heaped scorn on it in the Times, thinks it may

not answer the question that may be said to be the foundation of all

philosophy. Maybe so. But he tries. And he may be prophetic (an ironic word

given his views of religion) or he may be unable to prove his point. On the

other hand, he asks us to understand that our fundamental assumptions about the

origins of space/time may not have needed a push. If subsequent astrophysicists

can back him up he will then be given the Nobel if he is still alive or statues

and accolades if not. In any case, he is not headed heavenward, but tries to

bring the heavens down to earth inside our conscious understanding of the

nature of things, an echo of De Rerum natura perhaps.

****************************************************************************

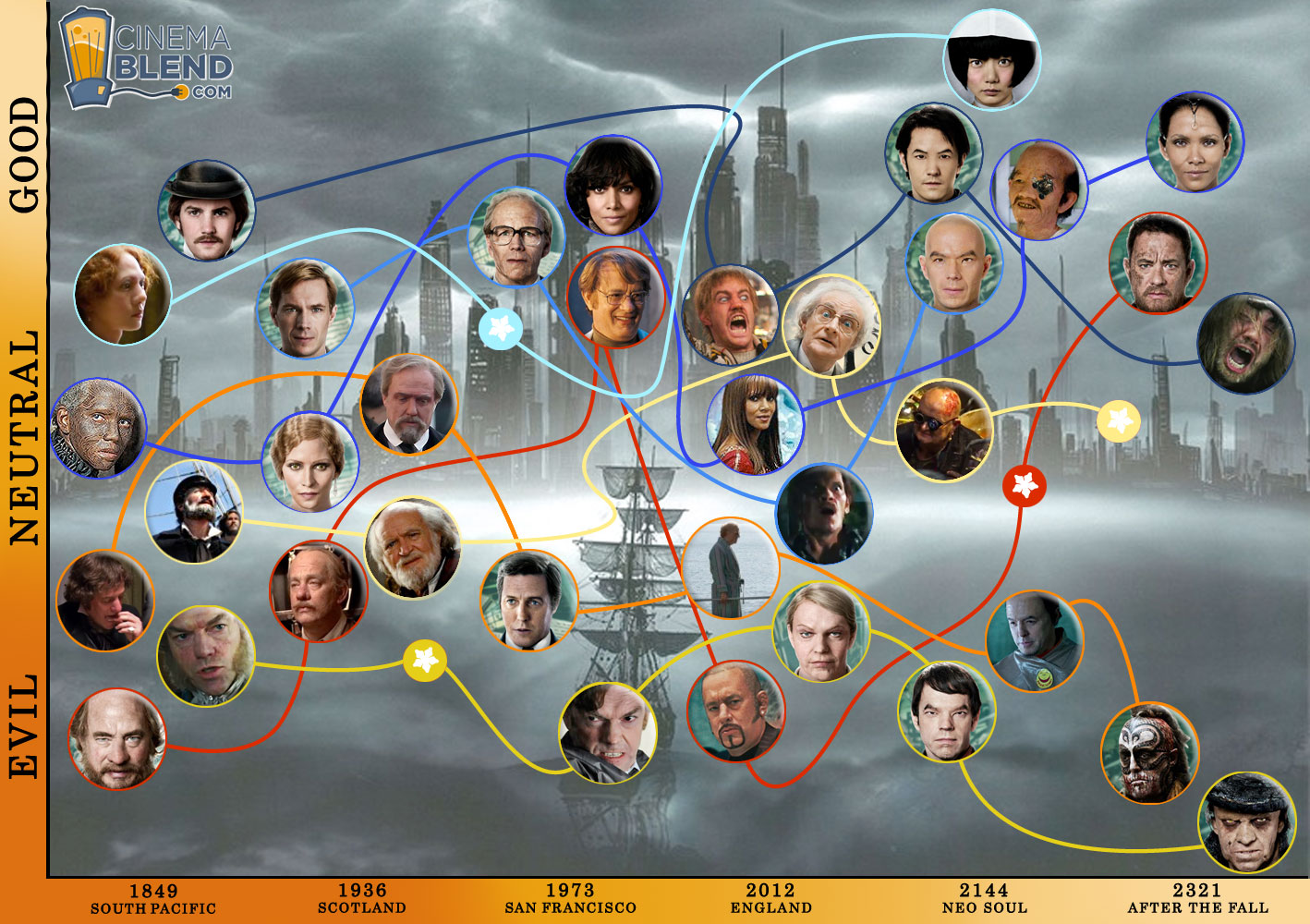

Engine Empire: Poems, Cathy Park Hong. If I had to think of an analogy

to this book of poems I would pick David Mitchells’ Cloud Atlas. Not the film,

but the book, in which the different eras call for different styles. Hong moves

from the founding of the American West to a future that is not wildly dystopian

but sad in its likely accuracy. She returns poetry to it roots in epic; rather

than stand-alone lyrics, she invokes images that permit us to share in a larger vision. The sequences form a whole and ask us to see across poems,

voices, and lines. By returning to the grand narratives of the past, she has renewed the call for poetry to be more than a block of print in a weekly or

monthly magazine. It participates in civic and poetic discourse and asks us to

think about the way words work to place us in worlds.

******************************************************************************

Try. Read. Write. These

are verbs and Constance Hale writes a wonderful book, Vex, hex, Smash, smooch: How Verbs Power Your Writing on how verbs are the gravitational center of the sentence. This book, along with her previous Sin and Syntax, are great primers for writers of any age. The title proves to be a set

of rubrics she uses to promote or dismiss good and bad prose:

Hex:

No to this

nonstarter: “Avoid passive constructions”

A hot of

experts rail against what they fuzzily call “passive constructions.” Sometimes

they mean we should avoid static verbs. Sometimes they mean we should banish he

passive voice. And sometimes they don’t even know what they mean…What do you

think Gabriel Garcia Marquez would have said to an editor who told him to change

the first sentence of One Hundred Years of Solitude? As translated by Gregory

Rabassa, it begins like this:

Many years

later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliana Buendia

was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to

discover

ice.

Here, in

one of the great opening lines of literature, the passive construction captures

the infinite passivity of Buendia’s situation.

All I can add is class dismissed. Great examples, like this one,

and great sentences from her pen too. Even some without verbs.

******************************************************************************

|

| Popular Mechanics Contest |

Jack Hitt's Bunch of Amateurs: A Search for the American Character is an optimistic celebration of those of us who still believe that great

innovations, discoveries, and contributions must come with a certain kind of

degree after or before one’s name. Hitt lovingly details those who are often

shunned by society until they are proven right and then those writers and scientists

fall all over themselves to say they knew ‘it” or him or her all along and were

just waiting for the rest of the world to catch up. In basements, garages and

blogs, people are making changes in the world. Sometimes almost alone. If we

had listened to the guys in garages we would not have had the housing crash we

did (see Michael Lewis’ The Big Short to see the outsiders (one literally in

his garage) had it right, while the big guys at Goldman ignored, overlooked or

worse, simply buried the bodies, that then surfaced.)

Hitt writes great sentences.

While the word

Amateur may be complicated and full of contradictions, the American amateurs

that constantly pop up throughout our history are, basically, one of two kinds

of characters. They are either outsiders mustering at some fortress of

expertise hoping to scale the walls, or pioneers improvising in a frontier

where no professionals exist. If every country forms its national character at

the trauma of birth, then we are forever rebelling against the king or lighting

out for the territories.

This last sentence is not simply beautiful; it entices us to

follow Huck Finn and the others who shun the traditional to find the

undiscovered countries of the soul, the soil, or the universe.

No comments:

Post a Comment