Yakube and Jemai were the most adorable children I had ever

seen in my life. Of course, they never told us their names, we had to derive

them from their yelps to each other between giggles. I could have continued

chasing them, limping and making elephant noises all day; it made me forget.

It made me forget the mortifying contrast between their condition and mine and

the contrast between their life-threatening concerns and my shallow teenage

dramas. I forgot about the burns on my arms from the hot metal plates of gravel

we passed to one another to build the classroom. I forgot about my hair, my

sprained ankle, and my now deformed sunglasses. All that was within my vision

was their cuteness, which drove me to momentary insanity: I was planning to

pull an Angelina Jolie and return to my parents in (name deleted) with a chubby

African 3-year old under each arm.

My crazy chasing and tickling fits with the two toddlers were

definitely some of the most beautiful moments of my trip to Tanzania. However,

the moment which served as the highlight of my trip was far from the cabbage

patches and tiny shacks we played around. It was not the moment I reached the

peak of Mount Meru or the moment I reached showers that did not discharge

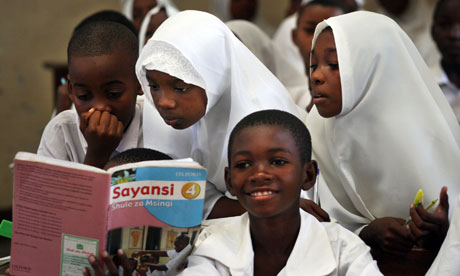

freezing water and tadpoles. Rather it was my first day in one of the crammed

classrooms of the public school, where almost one hundred children sat with

their eyes glued to my face. A mixture

of emotions fled though me at the sight of their willingness to learn. I can honestly

say that my singing and teaching in the classroom was the most moment of the twelve-day

itinerary, and maybe my life to date.

I may not have done as much as I could have; maybe I should

given more, taught more, felt more and worked more. However, I have never done

something so rewarding and self-satisfying. My time with the children of Tanzania

shall remain engraved in my memory for as long as I live. I gained their smiles

and respect and was able to spend time working with them, painting the walls of

their existing classrooms and placing a gravel floor in a new classroom which

shall accommodate another one hundred students who are eager to learn. Also, I

learnt much from the cultural pride of their tribe which is demonstrated in the

words of a young man I met near the school. He said to me, “If someone asks you

what tribe you are from, you can say, I am a Tanzanian.” Remembering their

words and smiles has made me become a far more positive person than I was,

prior to my journey. Don’t get me wrong, I may be seen complaining about my

school’s dirty toilet seat, but as a whole, I have learned to be much more

grateful for all of the fortune in my life.

This essay has gone through a number of drafts. How do I

know? The use of repetition in each paragraph is a structural principal that

makes the essay a literary success. It pulls us in by a series of rhetorical

flourishes.

It tells a story, gives details, and underscores a change of

perspective as a result of the 12-day trip to Tanzania. Given this should the essay be a positive

factor in the decision to admit this student to a highly college or university

in the US.

At 493 words, she

meets the rules of the game and, according to some of the books and articles

out there, she has successfully told a story that indicates she has grown

wiser, contributed to a community, and has exposed herself to a diverse world

and culture. What is not to like?

In a conversation with a world renowned anthropologist, he

let it be known to a rather large group of people that he considered trips like

the ones she describes as “poverty tourism” or "poorism". For him, trips like this do more harm than good to the indigenous people. He

said that these rich kids swoop in, get some exposure to poverty, swoop out,

and learn little about the culture and help very little in any significant

way. Is he right? And even if he is

right, does it matter?

The person who has been changed by the trip is not a young child, the village, or the school as much as the author. If the point of view has both

literally and figuratively been changed then is this enough to encourage students

to go on trips like this? If the essay is sincere, and to me it is, then this

trip was life altering. Perhaps she may go on and pursue her interest in this

field through her education and into her professional career. Does changing her life mean more than possibly altering the lives of those she spent time with in a negligible or even negative way?

A second critique of essays like this comes from some

admission officers who say it is unfair to reward experiences like this since

such trips are only available to those who have means. They argue that trips like this are expressly

taken so as to look good on college applications and therefore should not be used in any positive way. Is this a useful approach to essays like this? Again, I

would disagree. There are lots of different things one can do with time and

money. In this case, the student (and her parents) made a significant sacrifice

of both. In addition, the experience has been dramatic and life changing.

Should this be overlooked simply because not every applicant will have the same

chance? If this logic is followed through, then it would preclude a great deal

of the activities and experiences that applicants to selective schools present as positive. Most applicants and enrollees at highly selective schools come from upper middle class backgrounds. Playing lacrosse, starting a new

business, doing global service work are all expensive and therefore limit the

group of people who can participate. I would argue that if opportunities are

used to learn, then they should not be downgraded because they require

economic means. As I have said, some in admission offices strongly disagree with me.

The 3rd point I want to make about this essay is

contextual. I left out the location the student comes from for a reason. For this thought experiment, read the essay

again except this time include the name of the city: Compton, California. If this student came from what many of us

perceive to be a low income and less than ideal place to live would this alter

how one reacts to this experience? It should.

Now read the essay again and instead of Compton use Beverly

Hills. Does this change how a reader should interpret the significance of the

experience abroad? Should it? Is it then a shining example of poverty tourism

taken by a rich kid trying to stand out to selective schools?

Finally, insert the name of the true city this student comes from: Amman. This international student has taken a trip abroad and written

about it far better than most native speakers.

Should the ability to write this well in a second language be used to help

the student gain admission? Does the diversity an international student brings

be increased by an experience like the one she has described or is this too another

form of poverty tourism? Some in the US would think of living in Jordan as a

huge adventure with some risks involved. To her it is simply home. Does this serve as a teachable moment?

|

| Amman |

Does context-- place of residence and amount of available income, shift our reading perspective? Should it? It does, whether your answer to this

question is yes or no. Cognitive science

data and brain scans would demonstrate this.

No comments:

Post a Comment