|

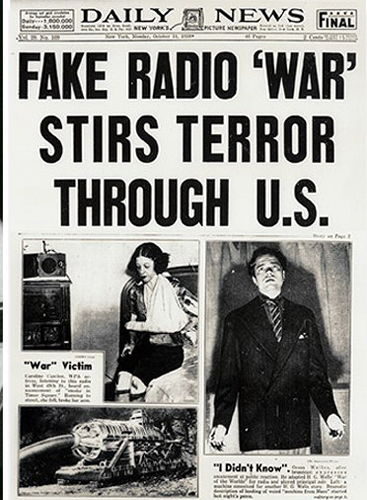

| Reaction to Orson Welle's Radio Broadcast |

There is a war going on. No,

not that one. Or that one. Or even that one. The war I am talking about today

is a war of words. The war is over a

relatively tiny bit on land. No, not that one either. It is the territory known

as the admission essay.

The two camps are often

adamant about the justness of their cause. They see the other side as

undermining the nature of writing as it is meant to be displayed on college

admission essays, college essays, and non-fiction essays in general.

Here are some quotes from a

few of the soldiers on the ground.

.jpg) |

| Lucas Cranach illustration of Luther's text |

******************************************************************************

Side A (descriptivist)

.

The personal essay has an

open form and a drive toward candor and self-disclosure. Unlike the formal

essay, it depends less on airtight reason than on style and personality, what

Elizabeth Hardwick called “the soloist’s personal signature flowing through the

text”.

Personal essayists converse

with the reader because they are already having dialogues and disputes with

themselves.

The personal essay has

historically sought to puncture the stiffness of formal discourse with language

that is casual, everyday, demotic, direct.

Part of your trust in good

personal essayists issues, paradoxically, from their exposure of their own

betrayals, uncertainties, and self-mistrust.

How the world comes at

another person, the irritations, jubilations, aches and pains, humorous

flashes—these are the classic building materials of the personal essay.

There is a fear of staleness

of cliché, or to put the matter more positively, a compulsion toward fresh

expression.

Georg Lukacs: “The essay is a

judgment, but the essential, the value-determining thing about it is not the

verdict (as is the case with the system), but the process of judging.

The essay challenges formal analysis by what Walter Pater called

its “unmethodical method,” open to digression and promiscuous meanderings.

Good essays are works of literary art. Their supposed

formlessness is more a strategy to disarm the reader with the appearance of

unstudied spontaneity than a reality of composition.

The essayist attempts to surround a something—a subject, a mood,

a problematic irritation—by coming at it from all angles. Wheeling and diving

like a hawk, each seemingly digressive spiral actually taking us closer to the

heart of the matter. In a well-wrought essay, while the search appears to be

widening, even losing its way, it is actually eliminating false hypotheses,

narrowing its emotional target and zeroing in on it.

The essay form as a whole has long been associated with an

experimental method. To essay is to attempt, to test, to make a run at

something without knowing whether you are going to succeed.

Adorno: “Luck and play

are essential to the essay”.

Barthes: “essay: an ambiguous genre in which analysis vies with

writing.”

On the other side, are the prescriptivists. The are the experts on advising how to fill in the formal elements of an admission essay, By experts, I mean those who are

publishing books and writing comments to students on forms like college

confidential. They have the backing of

some powerful educational institutions.

“The formal structure of writing has been described in this way:

Tell ‘em what you’re gonna tell ‘em

Tell ‘em

Tell ‘em what you told ‘em.

This is a good way to think of your writing… You have been taught

this structure and it is just what you need for the college essay.”

A more substantive piece outline of how to approach the college

admission essay comes from Robert Cronk. In his book "Concise Advice". He and I

both use movie metaphors in describing the approach to the essay although I actually

use the shortened version of a TV commercial. In other words, we share some

common ground in our use of metaphors.

Here are his steps to writing an effective essay:

Step 1 Close your eyes and walk down memory lane

Step 2 Make a list of those moments that stand out

Step 3 Close your eyes and visualize yourself back in those

moments

Step 4 Describe Those Moments in Words

Step 5 Determine what each of hose moments meant to you

Step 6 Choose one of the moments for your essay and turn your

description into a polished paragraph

Step 7 Write the end of your essay

Step 8 Fill in the in-between

Step 9 Polish the essay

Step 10 Let others read it

In both of the examples above, the writers offer concise advice

on how to structure the essay so that it communicates logically and

clearly. They offer what I would call a template

that permits writers to follow a path that will organize the words and

story.

A step-by-step approach offers some significant advantage; it is

relatively simple to follow and permits virtually any topic to fit within the

guidelines.

For those writers who are seeking a path through the endless

labyrinth of words this advice may be best. For those who love to wander within

the labyrinth and find the maze a game worth playing then this approach may not

be best.

|

| Jorge Luis Borges |

*********************************************************************************

Another way of describing the differences in the advice given in

Side A and Side B would be to appropriate the terms used to describe the two

poles of what has become known (among a very small group of people who even

know about this sort of stuff) the Grammar Wars. The argument is between prseciptivists

and descriptivists.

Here is a concise distinction, courtesy of the website: Motivated Grammar:

"Descriptivism,

in brief, is looking at what people say in a language and building up grammar

rules from that. Prescriptivism, again in brief, is having a series of rules to

tell you what should and should not be said. The difference in opinion between

descriptivists and prescriptivists is often referred to as a “war”. I’m

reluctant to say that’s overblown, because the gap between the two philosophies

really exists and really is wide."

On Side A, the approach to essays is primarily descriptivist. It does not work

from rules as much as it underscores the incredible variety of approaches (or

what I call voices) that work in creating an effective essay. In Side B, the

emphasis is on function-- rules or steps to follow in order to follow the

standard practice of writing as it is taught in most secondary schools.

The

set of questions that arise are:

Is

one of these approaches more effective for students writing admission essays?

Is

one approach more effective for those writing college essays?

Is

one approach more effective for writing essays they hope will be

published?

Are

some of these questions antithetical? I

Is

there room for compromise? A peace process, a solution that everyone can walk

away from with something like dignity and even, mirabile dictu, inspiration?

Comments

would help me answer these questions for myself if no one else.

In

the meantime, here is a flash essay excerpted from a very long essay on grammar,

and meaning, and writing. 499 words for nerds.

From one perspective, a certain irony attends the publication of

any good new book on American usage. It is that the people who are going to be

interested in such a book are also the people who are least going to need

it—i.e., that offering counsel on the finer points of US English is preaching

to the choir. The relevant choir here comprises that small percentage of

American citizens who actually care about the current status of double modals

and ergative verbs. The same sorts of people who watched The Story of English

on PBS (twice) and read Safire’s column with their half-caff every Sunday. The

sorts of people who feel that special blend of wincing despair and sneering superiority

when they see EXPRESS LANE—10 ITEMS OR LESS or hear dialogue used as a verb or

realize that the founders of the Super 8 Motel chain must surely have been

ignorant of the meaning of suppurate. There are lots of epithets for people

like this—Grammar Nazis, Usage Nerds, Syntax Snobs, the Grammar Battalion, the

Language Police. The term I was raised with is SNOOT. The word might be slightly self-mocking, but

those other terms are outright dysphemisms. A SNOOT can be loosely defined as

somebody who knows what dysphemism means and doesn’t mind letting you know it.

I submit that we SNOOTs are just about the last remaining kind of truly elitist

nerd. There are, granted, plenty of nerd-species in today’s and some of these

are elitist within their own nerdy purview (e.g., the skinny, carbuncular,

semi-autistic Computer Nerd moves instantly up on the totem pole of status when

your screen freezes and now you need his help, and the bland condescension with

which he performs the two occult keystrokes that unfreeze your screen is both

elitist and situationally valid). But the SNOOT’s purview is interhuman life

itself. You don’t, after all (despite withering cultural pressure), have to use

a computer, but you can’t escape language: language is everything and everywhere;

it’s what lets us have anything to do with one another; it’s what separates us

from animals; Genesis 11:7-10 and so on. And we SNOOTs know when and how to

hyphenate phrasal adjectives and to keep participles from dangling, and we know

that we know, and we know how very few other Americans know this stuff or even

care, and we judge them accordingly. In ways that certain of us are

uncomfortable with, SNOOTs’ attitudes about contemporary usage resemble

religious/political conservatives’ attitudes about contemporary culture. We combine a missionary zeal and a near-neural

faith in our beliefs’ importance with a curmudgeonly hell-in-a-handbasket

despair at the way English is routinely defiled by supposedly literate adults. Plus a dash of the elitism of, say, Billy Zane

in Titanic—a fellow SNOOT I know likes to say that listening to most people’s

public English feels like watching somebody use a Stradivarius to pound nails. We

are the Few, the Proud, the More or Less Constantly Appalled at Everyone.

|

| plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose |

No comments:

Post a Comment