Do we

need class warfare in the country? Those who participated in the Occupy Wall Street

movement thought so. But the battle lines are being drawn for a new battle that

will take place at selective colleges and universities. You may be surprised to

find out who stands to win and who stands to lose. I have written about this

before, but I will attempt to address the issue from the perspective of schools

and the perspective of those individuals who will find their efforts and hard

work will not being enough to stand out among those who are part of favored

groups.

There

have been a large number of articles recently focused on the plight of

low-income students. A number of studies just published indicate that students

who are low income and are in the top of their high school classes and who have

SAT scores in the top 10% of the national pool are not being recruited by the

top colleges and universities in the US. One of the articles, from Inside

Higher Education, grabs our attention by

demonstrating that even valedictorians who are low income and who fall into the

top 10% for SATs are not being sought out by the most selective schools in the

country. The way this article and others like it present the information, it

appears that schools are willfully ignoring these students. Having worked in

selective admission and having read thousands of exceptional student applications

from all economic levels, I would propose that while there may be some use to

getting selective schools to reach out more effectively to some of these low

income studens, the data behind the hype demonstrates that schools may actually

be doing that correct thing by not encouraging students to apply who have

little chance at being accepted.

This

article does raise some important issues, but at the same time does not report

important data which would help clarify why so many economically disadvantaged

students are not being recruited to the most selective colleges and

universities in the U.S.

The

first set of data that is not mentioned centers on the number of applications

submitted to top schools from the best students from around the US and around

the world. With applications topping 30,000 at some Ivies and other top

schools, the competition for spaces has increased dramatically in just the past

5 years. Acceptance rates are now below 10% at most of these schools. The

percentage of students who are not accepted who are valedictorians, whether

economically disadvantaged or not, is in some cases quite high—over 50%. It

should come as no surprise then that many of the students in this study are not

competitive for admission in such a strong pool of applicants. It does not indicate that there is any bias against this group of students.

College / University Overall Admit Rate Total Applicants Accepted

Brown 9.16% 28,919 2649

Columbia 6.89% 33,531 2,311

Cornell 15.15% 40,006 6,062

Dartmouth 10.05% 22,416 2,252

Harvard 5.79% 35,023 2,029

Princeton 7.29% 26,498 1,931

U. of Pennsylvania 12.10% 31,280 3,785

Yale 6.72% 29,610 1,991

The

second set of data points worth examining are the group statistics of the

students in the study: Students who self-report their grades as A- or higher

and have SAT scores in the top 10%. In a vacuum these stats sound quite good,

but measured against the applicant pool they are nothing special. A Critical Reading

score of 650 places a student in the top 10% nationally. A glance at Harvard’s

SAT average demonstrates that a score in this range is well below their average

of 697. The same holds true for each of the other subset scores on the SAT. Top

10% scores, in other words, are actually quite low in the pool of applicants to

places like Harvard. In

addition, students who are admitted to Harvard more often than not, have

staggeringly challenging academic programs.

What the

study does not report, and I do not think asked for, were the number of

Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate classes the students took in

secondary school. Schools in low income neighborhoods still often offer Aps but

not nearly at the rate of strong suburban public schools or any of the top

private and boarding schools. It is no longer unusual for students admitted to

top schools to have completed 10 or more AP courses by graduation. The number of

low-income students who have completed this number of AP courses is, I am certain,

very small. And for those who do, the numbers who earn scores of 4 and 5 would

be even smaller. Academic program is closely tied to academic success and yet

the study does not attempt to provide statistical information on this critical

assessment tool. To leave this out of the research is to skew the findings in

ways that makes it appear that selective schools are not adequately interested

in enrolling low-income students.

Finally, a premise the research

starts with needs to be examined. The current rush of articles and papers on

how low income students are being overlooked falls in line with what many other

attempts to rectify disparities from above often do—transform individuals into

statistical groups. Clumping individual students into a subset is sometimes

useful and sometimes not. In this case, I think it is a little of both. What

the article leaves out, for example, are the racial characteristics of

low-income students. A glance at the data demonstrates that 75% of the

low-income pool is white and 15% are Asian. 85% of these students, if they are

grouped in with other people of the same race, have to compete with the top of

the top of the applicant pool as an aggregate.

If all

those who were admitted because of some special ties to a favored group—under-represented minorities, legacies, athletes, development cases, children

of faculty etc.—then the SATs and academics rubrics based on performance would

be significantly higher than they already are taking the applicant pool as a

whole.

Let us

suppose, as a thought experiment, that the pressure being put on selective

schools to admit more low-income students works. What will happen? Another

group will then, from here on out, be measured and reported on each year. A

school’s commitment to this group will be measured by rising percentages of the

group. Raises will go to those deans who accomplish this. But at what cost? I

use this word 'cost' in its economic and metaphoric sense. Admitting low-income students at higher rates also means supporting them economically. Given full grants

to even 20 students a year amounts to over a 1 million dollars given current

tuition rates. A million dollars every year that does not go to salaries or

program or anything to do with the classes means that funds have to be found

that do not support the primary academic mission of the school. Need based aid

fundraising is one of the more difficult areas for development offices. People

would rather give to something with their name on it be it a building or a

merit scholarship.

Endowments are large at top schools

but many assume that money is readily available. For many top schools, this is simply not the case. Budgets are

tight when it comes to the day to day running of any university. The cost here

may be to expanding academic programs or hiring more faculty, but there will

have to be trade offs if a commitment is made to increase, significantly,

low-income students' presence on any campus.

The

other cost is to the other groups. If more spaces are allotted to low-income

students, this means that some other groups will have to suffer losses. Unless

a decision is made to increase the enrollment, it is a zero sum game. And who

will be the losers? It is very unlikely that the other special groups will take

the hit. If schools lower the number of legacies, athletes, under-represented

students etc., then there will be consequences either in terms of alumni

support or in terms of appearing negligent of racial diversity.

If not

them, then who? The ones who are already being squeezed the most, the people

who are the brightest groups of students-- upper middle class Whites and

Asians. The Ivies already have a defacto quota for Asians. The charts published

in the NY Times and other places detailing this phenomenon statistically seem

to provide convincing proof of this. Should an Asian student with 2400 SATs,

perfect grades, and over 10 APs be denied in favor of a low income Asian with

lower scores, a weaker program, and costs to bear? So too for white students.

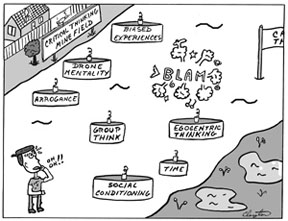

If

schools are going to be measured by their ability to enroll more and more

targeted groups, then the idea of a relatively fair holistic evaluation of each

applicant must suffer. The students who have done everything right and are

nearly perfect in every way except for not being part of a favored group will

be the ones not admitted. Maybe this is the way education should work at our

most selective schools, however, it seems very far from the premise that

individuals are what matters most in the world of admission in the world at

large.

No comments:

Post a Comment