The following is my

response to a question I was asked on Quora.com

Most of the books, articles and comments about Affirmative

Action generate lots of heat but little light on what it is, how it’s really

used, and what it means to individuals groups, and schools.

On the surface, such controversy seems odd. After all, the law seems pretty clear on what AA is supposed to be. In the multiply split decision that addressed Affirmative Action, the famous Bakke case, Justice Powell tried to weave a delicate balance that would permit the use of race, but in limited ways that took each student’s individual application into consideration. In doing so, however, his less than perfectly clear language permitted actions that have caused controversy ever since. The wiggle room that still exists means that there is no possible way I can address your question to define ‘exactly’ what affirmative action is. If I, or anyone else could, then the issue would be much less divisive than it was and still is. Today, more than ever, no one really knows what it means in general and precious few know what it means at particular colleges and universities.

On the surface, such controversy seems odd. After all, the law seems pretty clear on what AA is supposed to be. In the multiply split decision that addressed Affirmative Action, the famous Bakke case, Justice Powell tried to weave a delicate balance that would permit the use of race, but in limited ways that took each student’s individual application into consideration. In doing so, however, his less than perfectly clear language permitted actions that have caused controversy ever since. The wiggle room that still exists means that there is no possible way I can address your question to define ‘exactly’ what affirmative action is. If I, or anyone else could, then the issue would be much less divisive than it was and still is. Today, more than ever, no one really knows what it means in general and precious few know what it means at particular colleges and universities.

A couple of things people often forget about the Bakke case. First off, the Supreme Court actually struck down the use of quotas that were then in effect; in addition, the plaintiff, Alan Bakke, was then permitted to become a physician. In other words, from the standpoint of action, the Court ruled that schools could not use quotas to create greater racial balance on campuses. But here is where all the problems started. Justice Powell’s opinion became the template that was used by schools to move ahead with their efforts to diversify campuses. Schools took his words that said they could use race as a plus factor in admission decisions. By plus factor, Powell stated that if candidates were quite similar in most areas of academic preparation and perhaps some other factors too, then race could be used to tip things in the direction of minority students. To me, the use of race or almost anything else as a tiebreaker seems fine. Schools use all sorts of factors to create a diverse class—geography, economic background, special talents, great essays, activities etc. A slight push for diversity that was used in the ways these other factors often were would not have raised much of the furor that still goes on every day somewhere around the media.

But here is when things get complicated and murky. Schools wanted to diversify their student bodies, but were no longer permitted to do so by means of the easy method of quotas. But the sad fact was, and still is, that without firm quotas like this, there are some groups that lag so far behind others in academic preparation that using race as a plus factor would drastically reduce the percentage of minority students in their incoming classes.

Chris Rock: warnng--graphic language

Here’s some data that might help support this assertion. At what many think is the top high school in the US, Thomas Jefferson in Fairfax, VA, they use an entrance exam to determine who gets accepted. A glance at the demographics of the students demonstrates there are woefully few under-represented students. There have been years when there were barely a handful of African American students in the class. Testing is used by a number of magnet schools like this and the demographics are much the same.

Here’s some data that might help support this assertion. At what many think is the top high school in the US, Thomas Jefferson in Fairfax, VA, they use an entrance exam to determine who gets accepted. A glance at the demographics of the students demonstrates there are woefully few under-represented students. There have been years when there were barely a handful of African American students in the class. Testing is used by a number of magnet schools like this and the demographics are much the same.

Selective colleges and universities rely on testing too but

they incorporate a far more complicates system to determine who gets accepted.

In the very useful book “No Longer Separate, But Not Yet Equal”, the authors

use data from huge swaths of the college going population to evaluate the

different performance rates between races and income groups. It may be the best

resource that I know of to show how wide the achievement gap is between some

groups and others. There is just too much good data there to dismiss it as

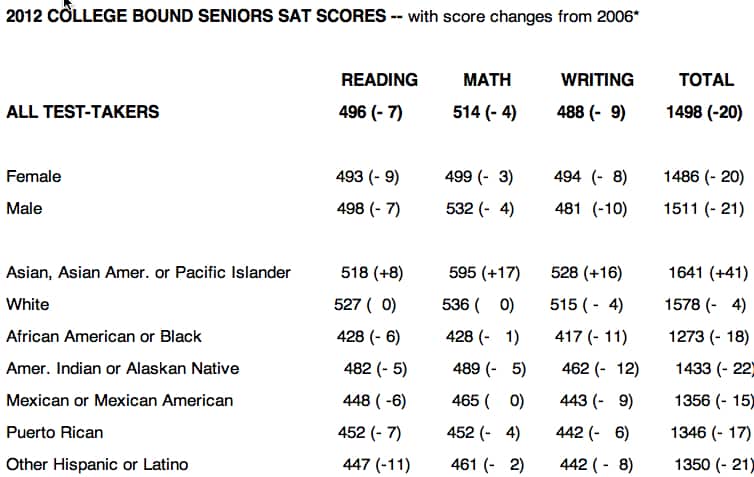

misleading. Currently, African American

students tend, on average to score at least 150 points lower on the SAT than

white students. Lots of people in education say SATs are not great measures of

academic success. This is correct (The College Board itself says this again and

again) when it comes to comparing people whose scores are close. But a gap over

150 points is significant and does predict that performance will vary with

scores this far apart. In addition, there is a little known data point out

there: SAT scores actually over predict the performance for African American

students in college.

While the standard meme on SAT testing is racist, this does not explain in any way that SATs over predict performance for the group that the test is supposedly racist against. In addition, if the test is racist, then it should hurt minorities across the board, but it doesn’t. Asians actually score higher than any group. Why would Asians be able to perform better than anyone else if the test is racist toward non-whites? I’ve yet to see any data that could explain this scientifically. In addition, there is the feeling that Asians are a part of the middle class or higher and thus have the resources and attend schools that would prepare them to do well on things like the SAT. But again there is data to undermine this assertion too. Berkeley and UCLA have almost 50% Asian populations (higher if they included international students, a group that is largely Asian but don’t count as Asians as that is the way some schools report percentages of students). These two schools also have nearly 40% of their incoming class eligible for Pell Grants—they are far more successful than any top schools in enrolling low-income students. Many of these low-income students are Asians. Testing then becomes problematic not because it is racist, (it is a pretty good predictor of success), but because it hurts those groups of students that schools wish to enroll in higher percentages. And SATs are not the only problem. The dean of admission at Harvard says the best predictor of success-- scores on AP exams. But if schools used this measure equally for all students, then under-represented student percentages would plummet. A not insignificant percentage of under-represented students attend schools that offer few APs; even when they do, the performance of the students on these tests is often low. But even affluent and middle class under-represented students have scores and academic programs that fall far below their peers. The issue, in other words, is not only one of class.

To sum up, testing, academic program and performance in a tough AP or other demanding programs help predict success in college. The data is pretty clear about this. But some groups do not have the performance to compete near the level that using race, as a tiebreaker, would help. The gap is too wide. So schools have, in some cases, abandoned any pretense of using race as a tiebreaker. It is determinative. However, since this goes beyond what the Supreme Court says they should do, schools have to get creative.

Creative means different things to different people in education. For some it means finding ways of demonstrating that factors like testing, academic program, and performance are not determinative to predicting success. This is where the holistic evaluation of applications comes in. Holistic means that there are far many other factors that come into play in a decision to admit students. Holistic can be used positively or negatively. In the 50’s, the Ivies turned to holistic admission in large part because too many Jewish students were doing well on the SAT and too many were getting in to these schools. (See the book "The Chosen" for all the dirt and data about this sad time in education.) But now holistic evaluations are used to bump up students who are primarily members of under-represented groups. (Or bump down one group—Asians.)

But a bump is one thing and a huge shove another and that is what all the fuss is about. There are simply not enough strong students who are members of certain groups for schools to enroll enough of them to keep the percentages of under-represented groups close to what they would like to have. Some schools say they want a population that mirrors the racial demographics of the US population as a whole, or, in the case of state schools, the population of the given state. But this means that in order to accomplish this they often have to dip somewhat deep in terms of academic measures. This is where the test gap comes in. Many under-represented students who do not attend the most elite of the elite schools (Harvard Stanford etc.), have credentials that are not infrequently below those of others. It is no surprise then that many of these students don’t do often excel academically at these schools. Many of them graduate, but their gpa’s can suffer and this hurts their chances to get into graduate schools or earn interviews at companies that use computers to cut out applicants by gpa. There is an achievement gap between the performance overall between under-represented students and whites and Asians in high school and this continues on through college But this gap in college performance should come as no surprise. And this gap does not, I think, support claims that professors and institutions are racist. If these students are coming in behind the other students it would seem likely they would leave the same way. And they do. Only this data about performance rarely gets much press except in what most would call the conservative media. In part, transparency about performance and race might serve to undermine the outreach efforts on the part of schools to enroll higher percentages of certain groups. If there is data that shows that some groups don’t fare all that well academically in a particular school, students who are part of these groups might not want to attend the school. It is a tough position for the schools who want to recruit underrepresented students and it is tough for the students who don’t have access to good data.

The Individual student, however, is often left out of the determination as to whether the policy of dipping down on academic performance for certain students in itself is in that particular student’s best interest. From the outside, the schools who enroll a significant percentage of certain groups of students get good press for having what has at times been called a critical mass—a percentage of students who are part of a group that comprise a large enough number so the school looks good when it comes to comparisons between schools. There is almost no data on what percentage might actually comprise a critical mass, but it tends to be used to say that the percentages of certain groups need to be increased as very few selective schools have percentages of under-represented students that match the overall population rates.

Schools rarely release data on performances of racial

groups; this kind of data would then lead to discussions that would question

whether the schools are actually following the law. A tiebreaker is one thing

but using race as a determinative factor another. There are areas of grey, of

course, about which is which and how much all this occurs at individual schools.

But the figures show that at many schools race certainly seems to be the

determinative factor. If this is so, then admission offices have extended their efforts to enroll a

diverse class in ways the Supreme Court

has not explicitly approved. It also means that (if some of the studies are accurate),

unrepresented students who are given a big boost to get into certain selective

schools often have to change their future career plans. "Mismatch," a

book about students who are admitted with academic credentials far below other

students, has data that purports to demonstrate that underrepresented students

who are in STEM fields and competitive pre-professional programs frequently

drop these majors (they still graduate however). The authors say the students

should have attended a less selective school where their credentials would have

matched their classmates and that in these places, also good schools, they

would have not had to compete on an uneven playing field. The data about this

looks pretty compelling to me. To expect a student who is two years behind in

class prep in math and has 150 deficit on testing to compete at a high level in

premed or engineering courses does not make a lot of sense.

But this in fact happens. Schools are much more focused on getting percentages of underrepresented students to show up on a profile than they are in making sure they are prepared to compete in the areas they wish to pursue in life. Nevertheless, schools continue to do all they can to increase percentages of underrepresented students. After Prop 209 passed in California, the state schools embarked on recruiting great under-represented students who would qualify for the automatic admission to the system. Again they ran into the data that showed there simply were not enough of these students. They then incorporated a holistic system for a percentage of students admitted and many of these students are under-represented students. An article that appeared this year in the NY Times from an application reader there made it clear that while the word race is not used in open discussions it nevertheless has a significant role in admission decisions.

While this may seem a huge digression, I hope that it isn’t. In the two Supreme Court cases against Michigan a decade ago, the court struck down the point system which automatically awarded a set of points to applicants based purely on race. This mirrors what they did in Bakke. However, the Court again ruled that schools have a compelling interest in having a diverse student body and that this meant that race still could be used as a tiebreaker. Since then however, Michigan passed a ban of using race, and there is another case before the Supreme Court now examining whether this law is legal. Hearing the recent remarks by the judges, it seems unlikely they will overturn the state law.

But this in fact happens. Schools are much more focused on getting percentages of underrepresented students to show up on a profile than they are in making sure they are prepared to compete in the areas they wish to pursue in life. Nevertheless, schools continue to do all they can to increase percentages of underrepresented students. After Prop 209 passed in California, the state schools embarked on recruiting great under-represented students who would qualify for the automatic admission to the system. Again they ran into the data that showed there simply were not enough of these students. They then incorporated a holistic system for a percentage of students admitted and many of these students are under-represented students. An article that appeared this year in the NY Times from an application reader there made it clear that while the word race is not used in open discussions it nevertheless has a significant role in admission decisions.

While this may seem a huge digression, I hope that it isn’t. In the two Supreme Court cases against Michigan a decade ago, the court struck down the point system which automatically awarded a set of points to applicants based purely on race. This mirrors what they did in Bakke. However, the Court again ruled that schools have a compelling interest in having a diverse student body and that this meant that race still could be used as a tiebreaker. Since then however, Michigan passed a ban of using race, and there is another case before the Supreme Court now examining whether this law is legal. Hearing the recent remarks by the judges, it seems unlikely they will overturn the state law.

Which brings us to the most recent court case out of Texas. After hearing the judges respond to oral arguments, most educators thought affirmative action would be overturned. Instead, the judges turned the case back to the lower courts and said the schools that wish to employ affirmative action need to demonstrate that they have tried other remedies before just using race. This decision has made what individual schools do with affirmative action problematic. Have schools actually tried other programs that attempted to get a diverse class that was not tied to race? Some have, but most have not. If the schools wish to avoid litigation they may bend a bit on what they’ve been doing with affirmative action. Or they may try to spend huge sums of money to promote diversity that will get the students they want within the limits of the law. However, most schools are budget strapped so this does not seem something that will happen.

Finally, the Obama administration last week issued comments that said that they support affirmative action the way it has been carried out over the previous generation. Opponents see this as tantamount to telling schools to ignore what the Fisher case seemed to say. On the other hand, are many schools willing to face lawsuits from students who will have data that demonstrates schools have not done much of anything to find alternatives to affirmative action? Lawyers tend to be risk averse so I imagine that many schools may be at least a little more careful about how low they will go in selecting some students.

Your question comes at a time when almost no one is exactly sure what is or is not permissible when it comes to affirmative action. In the Michigan case, O’Connor wrote the opinion and she said its shelf life is 25 years. 10 of those are gone and yet there has been almost no significant movement in the achievement gap. Despite billions invested in all sorts of education reform, there has been little change in the gap except for Asians. Few know that the Bakke case included Asians as a group who would benefit from affirmative action. Now, however, Asians have to have much higher scores than whites in order to be admitted to Ivies. As the stories out there ask: Are Asians the new Jews? A good question I think. (I have raised this issue on Quora and on this blog. The racism against Asians seems to be there for all to see, but there is little done as they are thought to be a model minority and so are not in need of help.)

Schools think they are doing the right thing to promote social justice and societal change by admitting students who are, upon occasion, not close to tiebreaker status. Others see these efforts as illegal and actually hurtful to the students who are the supposed beneficiaries. The problem could be addressed much more effectively if schools opened up their data for studies on performance and future success. But schools have not been forthcoming with the data. Not surprisingly, this reticence leads critics to believe schools have something to hide. And if this is accurate to any significant degree and schools are then hauled into court, then they may well be exposing themselves to huge penalties. But my guess is that schools will continue to figure out ways to use race in the ways that they want to unless a definitive decision comes in from the Supreme Court. The justices have been hesitant to do this again and again so it may be that over the next 20 years the landscape will remain blurred, but maybe by then things will have changed in education so there are more underrepresented students who are doing well enough that affirmative action will be no longer necessity. I don’t believe this and I really think almost anyone in education today is skeptical too. The systemic issues are too great and there are too many issues that cannot be talked about in public.

The closed doors of admission offices will remain largely closed. This issue is just one of many that if ever the accurate story were told things would not go well for some people or institutions. Admission offices are largely rewarded by the groups they bring in rather than by the individuals who should be looked at on a case-by-case basis. As long as this is so, closed doors and lack of data will be what we can expect unless cherry picked data is used to support an issue they support. There is a great deal of data out there on these issue but precious little of it would qualify as signal rather than noise (Read Nate Silver’s great book "The Signal and the Noise") In my personal opinion, if deep data studies were conducted across schools, races, and majors I believe that affirmative action as it is currently used would have to change. As to what a school like Swarthmore does, for example, is not something you could find out without getting open access and that is unlikely to happen for the reasons I’ve stated above. How Swarthmore or any school approaches the issue will now, because of the uncertain landscape, be slightly different in range and scope than many other schools. Selecting students to schools has always been both art and science, but right now there are lots of experiments going on in hundreds if not thousands of schools. Maybe a few will come up with a solution that will help everyone.

|

| Happy Birthday Kurt |

No comments:

Post a Comment