In Part I of a philosophical examination of how schools

choose an ‘ideal’ student I questioned the usefulness of holding up an impossible

Platonic model for students to compare themselves to.

Plato was around for 2000 years before the US came into

being. But the latecomers to the world of thinking came up with something I

would encourage schools, students and just about everyone else to think about. C.S. Pierce and William James, a little over a

century ago, founded a school of philosophy called Pragmatism. They dismissed

the Platonic ideal as an unsuccessful and at times harmful way to measure the

world. Instead of playing with Plato, they dismissed his Ideal and posited a

new approach: is something, even something imperfect, as all things in the

world must must be, useful to a task or thought? If so, then it does not matter

whether it is even ‘true’ let alone an ‘Ideal'.

Why this mini-lesson in philosophy? Admissions officers are,

or at least should be, pragmatists rather than Platonists. Most admission deans

do not bother to look for the impossible—the ideal student—since he or she does

not exist. Instead they ask: Is this particular student useful to our

institutional needs? This questions

leads to decisions and thinking at odds with those who search for an ideal.

Let’s start with the basics. Admission officers work for a

particular school and the school has concrete needs. What these various and at

the same time specific needs consist of will largely determine the kinds of

students they accept. The needs vary

from school to school, but here are a few that almost all selective schools pay

attention to:

Richard Rorty

Pointy

Is a student smart? Smart is not easily defined but in

college admission it still gets quantified. As student taking challenging

course, earning top grades and doing well on a range of tests (SAT or ACT or AP

or IB or A level etc.), with strong teacher recommendations and strong support

from a school counselor ends up in the smart pile. Those having the top scores,

programs and performance are often accepted to selective schools largely based

on academic potential.

But there are different ways of demonstrating intellectual

promise and the old standby cliché ‘academic passion’. A student who has done

exceptionally well in the sciences, has performed research and taken part in

science competitions and received recognition often is not a great athlete will

stand a great chance of getting into top schools which offer engineering or

research based science. Almost all Intel semifinalists end up with great places

to go whether or not they’ve done all that much except prepare for this

competition.

Sometimes this

happens but it is rare. But admission officers are, as I have said, pragmatic.

They look at what strengths a student brings and evaluate them. If the school

wants great future scientists, then they may accept a student who has never

participated in a sport or never done all that much outside of his or her

passion. The common terms for this kind

of student is pointy, not as in the pointy-headed intellectual as pointy

describes other kinds of students too.

Instead, they create a class of student with different

talents, backgrounds, and worldviews. A student who is remarkably gifted as a

writer will be not be expected to be a science whizz kid too. But this writer

must compete against all the other students who have been identified as great

writers and must be near the top of the stack.

In other words, an applicant pool does not exist as an

aggregate to an admission office. This highly selective admission process

should be, at least in some ways, reassuring to students. One never competes

against the whole applicant pool. Rather one competes in the group one is

placed in.

Specials

On the other hand, some groups are much better to be in than

others. Legacies, under-represented students, all, to a lesser degree students

who demonstrate ‘grit tend to get a significant boost in the admission

process—just look at the acceptance rates for these groups for proof.

For example, a student who is a reasonably good student, but

who has the talent to bring home a championship in a sport the school loves,

will then go to the top of the pile of that subset of students.

Unspecials

Membership in some groups also means that the chances of

being offered admission to highly selective schools will be even harder than

the published school profiles often indicate.

Here are just two examples:

A person in admission for 3 decades I know well used to joke,

politically incorrectly, about how bad it was to be a “girl from New Jersey”

when applying to selective schools. It was not that he disliked the Garden

State or females. Instead, demographics came into play. There are thousands of

great female students in New Jersey who attend at great secondary schools.

Females do better than males academically and New Jersey is densely populated

but does not have a large number of state schools to keep them near home. Colleges cannot admit that they practice a

form of affirmative action for men but an article in the New York times from an

admission office at a liberal arts school admission officer admitted as much.

Schools want to keep a balance between males/female ratios even if this means

that they may hold females to higher academic standards. The same thinking goes

into school’s efforts to get geographical diversity. Schools who want a

national reputation need to show on their profiles that they draw students from

all across the country.

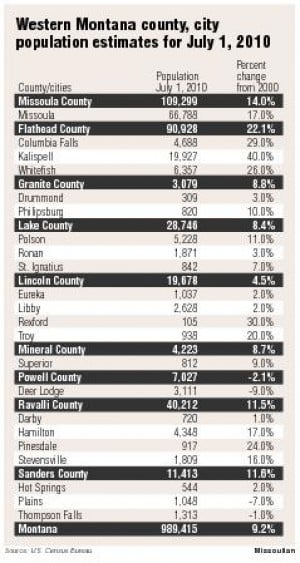

A student from Montana (the typical State named in discussions

about this form of grouping) stands a better chance of admission that a student

with virtually the same academic credentials from New Jersey. The thinking goes

like this: a student is more than scores. Growing up on Montana will affect the

thinking, experience, and outlook of an individual. Having people from

different places will make the overall educational conversation on a campus

more inclusive and wide-ranging. Whether this actually is measurable in any way

is another matter. Or whether someone from Montana is inherently more diverse

than someone from Teaneck or Trenton is a subject for debate, but at least at

present the place someone lives does affect the chances for admission. Given

that very few students apply from certain states to schools far away from hone

means that they will be measured against the best students from their state

rather than simply against the whole applicant pool. Some schools pay far more attention to

geography than others, but the chances of being admitted from Montana with

somewhat lower academic credentials are verifiable should the schools release

the data.

A student from Montana (the typical State named in discussions

about this form of grouping) stands a better chance of admission that a student

with virtually the same academic credentials from New Jersey. The thinking goes

like this: a student is more than scores. Growing up on Montana will affect the

thinking, experience, and outlook of an individual. Having people from

different places will make the overall educational conversation on a campus

more inclusive and wide-ranging. Whether this actually is measurable in any way

is another matter. Or whether someone from Montana is inherently more diverse

than someone from Teaneck or Trenton is a subject for debate, but at least at

present the place someone lives does affect the chances for admission. Given

that very few students apply from certain states to schools far away from hone

means that they will be measured against the best students from their state

rather than simply against the whole applicant pool. Some schools pay far more attention to

geography than others, but the chances of being admitted from Montana with

somewhat lower academic credentials are verifiable should the schools release

the data.

Students from China applying to Ivies face enormous

challenges. The stats show that Asians as a group have to earn significantly

higher scores on test in order to be accepted. But it doesn’t stop there for

students from China. Because schools limit the overall number of international

students they admit, those who apply from countries with huge numbers of

applicants face greater challenges. In some cases the acceptance rate for Chinese students to some schools are under 1%. Schools will

not publish this information as then fewer students would apply and that would

possibly mean they would miss out on a great student they wanted. Or more

realistically, it would mean their application numbers would drop and this

would hurt their selectivity ranking in the US News.

*******************************************************************************

Lots of people do not like the fact that schools choose

students based upon groups. But schools are not alone in favoring groups. We

all do it at some level whether in terms of friendships, jobs, or life

partners.

Colleges and universities stress that the admission process

is based on an assessment of each applicant as an individual. What I have

written here would seem to undermine this assertion, but things are not quite

so simple. Students are looked at as individuals but they are looked at as

individuals who are also part of groups.

The groups are divided in ways I have outlined but within

the groups students are given a close look for individual achievement and

abilities. I have said here before that the world exists far more on

the axis of both/and rather than either/or and in the case of groups vs. individuals

I would again ask that people looking to critique or learn about admission

understand that there is room for paradox and overlapping yet differing approaches.

Mutually exclusive thinking rather than pragmatic compromises

often predominates political thinking these days but the challenge of trying to

do many things well—bringing in lots of different great students with great

being defined differently, seems a good way to, as the pragmatist philosopher

said repeatedly affirmed, muddle through the infinite complexities of issues

and life.

In part 3 of this overview of what makes the best students I will attempt to examine another admission

paradox: for richer for poorer.

A great summary of how selective college admission (in my experience in admission and seeing it as a counselor) works. I think it's interesting, as well, to take a step back even further and question the American notion of who should be on a college campus. The "usefulness" you describe serves, it seems to me, to attempt to produce little utopias of sorts through an incredibly complicated and bewildering set factors to be judged by admission committees. I am a college counselor who works at a high school with a foreign curriculum, and I've worked at two high schools in other countries. Lots of my students apply to Canadian universities, where the only factors judged are academic ones: sometimes only grades, or sometimes a combination of grades and standardized test scores. There's no essay, no recommendations, just grades and the proper high-school courses needed. I have been on many Canadian campuses, and they are just as diverse-looking as their US counterparts whose admission officers have spent months haggling over legacies and athletes and minority students and pointy kids and bootstrappers. At least, this is true of the most well-known Canadian universities. So I have to wonder: is this ridiculously complicated American process really worth it? The American admission process speaks to the larger ideal of America, of the American dream, I think.

ReplyDelete