In a book filled with narrative profiles of people who we

accompany across a generational drive across decades of the American landscape

(It starts roughly about the time that Kerouac finished his ode to the road in America),

there are just a few pit stops for cited research or quotes from books. Near

the end of George Packer’s blurbally and mostly (David Brooks has issues with

it) book review lauded The Unwinding: An

Inner History of the New America, however, one profession and one text get

far more explicit detail than anything we have encountered before:

The

companies that hauled the oil away were called renderers. Besides restaurant

oil, renderers also collected animal carcasses— pigs and sheep and cows from

slaughterhouses, offal thrown out by butcher shops and restaurants, euthanized

cats and dogs from the pound, dead pets from veterinary clinics, deceased zoo

animals, roadkill. Mounds of animals were trucked to the rendering plant and

bulldozed into large pots for grinding and shredding; then the raw meat product

was dumped into pressure cookers, where fat separated from meat and bones at

high heat. The meat and bones were pulverized into protein meal for canned pet

food. The animal fat became yellow grease, which was recycled for lipstick,

soap, chemicals, and livestock feed. So cows ate cow, pigs ate pig, dogs ate

dog, cats ate cat, and human beings ate the meat fed on dead meat, or smeared

it over their faces and hands. Rendering was one of the oldest industries in

the country, going back to the age of tallow, lard, and candlelight, and one of

the most secretive. A book on the subject was titled Rendering: The Invisible

Industry. It was the kind of disgusting but essential service, like sewers,

that no one wanted to think about. The companies pretty much regulated

themselves, and the plants were built far from human habitation, and outsiders

were almost never allowed into one, or even knew it existed unless the wind blew

the wrong way. Renderers turned the waste cooking oil they collected into yellow

grease, but it had a different use than animal fat, one that the companies were

only just starting to figure out: because it jelled at lower temperatures than

animal fat and burned clean, the oil was ideal for making fuel.

It may be strange to use the word ‘epiphany’ to describe

this passage, but in a book that challenges assumptions and genres I think the

word fits. Why does Packer give us such

emetic detail? In part he wants to show from the humblest beginnings, from the

refuse of the world, great ideas might spring. Another way of saying this: it

is not the devil that is in the details but the salvation of this particular

soul: Dean Price, who, if there is a hero who summons our sympathy most often,

it might be him.

But Packer‘s details about rendering work at another level

too, what English scholars would call the allegorical. The Unwinding itself is an exercise in rendering. Although there

are profiles of well-known politicians (Biden comes off poorly but Periello

comes off as heroic), the majority of people we meet live in circumstances

ranging from homeless, broke, near broke, disappointed, disaffected, and

depressed. They are the inner history the title refers to, but they are also largely

the hidden history.

In

the unwinding, everything changes and nothing lasts, except for the voices,

American voices, open, sentimental, angry, matter-of-fact; inflected with

borrowed ideas, God, TV, and the dimly remembered past— telling a joke above

the noise of the assembly line, complaining behind window shades drawn against

the world, thundering justice to a crowded park or an empty chamber, closing a

deal on the phone, dreaming aloud late at night on a front porch as trucks rush

by in the darkness.

He gathers their stories and except in a few cases, creates portraits

that are rounded rather than flat. In doing so he gives what some of them seem

to have lost—dignity.

His effort then is perhaps quixotic too, taking these disparate

stories and putting them together to form a more perfect union. In the future, given

the unbinding of the Titans of mammon over the last generation, the hope for

better things to come rest not a an Olympian but on the hope that people like

Dean, the people largely ignored and often on very different ideological sides

might somehow find a local habitation and a name worth striving for. Packer

renders these people in many senses of the word, but mostly he renders them

with a fine writer’s craft and in so doing makes them both sympathetic individuals

and symbolic markers of millions.

Immediately after the climactic epiphany of the book, there

are several more references to texts, this time to words that are worldly and

extend back to the dawn of history. Packer jumps from a quote from Gandhi to a

parable taken from a 19th century preacher who filched it from a

Buddhist priest who filched it from a Persian farmer who is taking the Buddhist

on a tour of Nineveh and Babylon.[i] What

Packer does here is to extend the reach of his story of America back and

across. The story becomes mythic then, a tale told since the dawn of time and

told in cultures that extend all across the world. The story of the common man

and the common woman is also global too.

“This

goes back to Gandhi,” Dean said. He had bought a book called The Essential

Gandhi and read about swadeshi, which meant self-sufficiency and independence.

“Gandhi said it was a sin to buy from your farthest neighbor at the neglect of

your nearest neighbor. It’s not about mass production, it’s about production by

the masses.

Packer’s book is blurbed glowingly by Katherine Boo, whose

book, Behind the Beautiful Forevers, won

the national book award. I rated it as

one of my best books of 2012. Based on 3 years of on the ground research and

interviews, Boo details the lives of some of the lowest of the low in a

community in India. She also details the bureaucratic and political machinery

that promotes the cycle of poverty. Packer is not mimicking her approach but

both of them avoid what has come to be called

"Poorism." This word connotes a quick drive by by

wealthy people --poverty tourism. Both Packer and Boo give us enough details

about the people that they render and

that their words are artful enough to evoke.

After this brief foray into global connections, the

narrative picks up again as Dean Price embarks on an odometer-popping road trip

through the tiny towns of North Carolina, trying to sell his dream while trying

to bring local communities into contact toward participating, in a small way,

in the global economy. And this is where the book ends: with the man who has

had this education in rendering and who brings from it an entrepreneurial dream

which may prove, at some future date, prophetic or quixotic: “He still had a

dream of building a big white house and filling it with children. He would get

the land back.” These, the last words of the book, call to mind another dreamer

of a by gone era: Scarlett O’Hara. She brings the indomitable will when she has

lost it all. And there is another echo throughout the book too. The Wizard of Oz. The tag line there “there

is no place like home” runs underneath the Packer’s narrative. People move often

but just as often return if not home then at least to the city they were from. Lest

these references seem to belittle the importance of the book, I think these two

works helped shape and define what we now think of as the American Dream. The

film versions, released just 5 months apart during the Depression, both give

praise to the land, the farm, the home. Packer wants, if not a return to

Jeffersonian agrarianism, then at least a return to things that are made in the

world locally and that can be seen and felt and smelt, as we render them unto

the market.

Packer seems to imply the micro bits of information and

currency that moves across borders isn’t ‘real’ and neither are the lives of

those who have amassed billions of these bits.

But to quote from another American classic: “Isn’t it pretty to think so?”

But to quote from another American classic: “Isn’t it pretty to think so?”

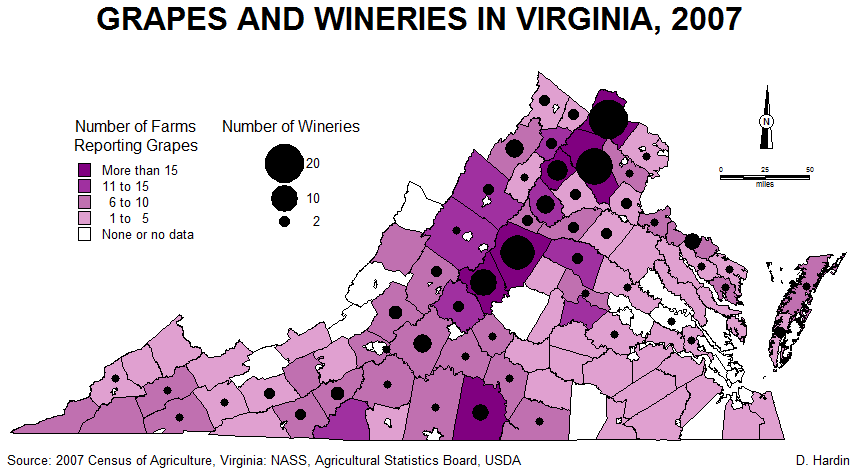

I write these words on July 4th, sitting on a

mountaintop in rural Virginia, the location of some of Packer’s book. The

fireworks have just ended and from my porch I could see bursts of color from 6

of the communities across 2 counties. Maybe these communities will continue to

redefine themselves: more and more local people cultivate wineries and

vineyards throughout the area so at least here, tonight, it really is pretty to

think so.

[i] On his bookshelf there

was a volume called The Prosperity Bible, an anthology of classic writings on

the secrets of wealth. Dean’s second favorite after Think and Grow Rich was

Acres of Diamonds, a lecture that a Baptist minister named Russell Conwell

first published in 1890 and that he gave at least six thousand times before his

death in 1925. Conwell had been a captain in the Union army, dismissed for

deserting his post in North Carolina in 1864. He went on to write campaign

biographies of Grant, Hayes, and Garfield, and later became a minister in

Philadelphia. The lecture that made him famous and rich— rich enough to

establish Temple University and become its first president— was based on a

story Conwell claimed to have been told by an Arab guide he hired in Baghdad in

1870 to take him around the antiquities of Nineveh and Babylon. In the story, a

Persian farmer named Al Hafed received a visit from a Buddhist priest, who told

Al Hafed that diamonds were made by God out of congealed drops of sunlight, and

that he would always find them in “a river that runs over white sand

between high

mountains.” So Al Hafed sold his farm and went off in search of diamonds, and

his search took him all the way to Spain, but he never found any diamonds.

Finally, despairing and in rags, he threw himself into the sea off the coast of

Barcelona. Meanwhile, the new owner of Al Hafed’s farm took his camel out for

water one morning and saw in the white sands of a shallow stream a flashing

stone. It turned out that the farm was sitting on diamonds— acres of them— the

mine of Golconda, the greatest diamond deposit in the ancient world. There were

two morals in Conwell’s lecture. The first was provided by the Arab guide:

instead of seeking for wealth elsewhere, dig in your own garden and you will

find it all around you. The second was added by Conwell: if you are rich, it is

because you deserve to be; if you are poor, it is because you deserve to be.

The answers lie in your mind. This was also the thinking of Napoleon Hill, the

belief that there was divinity in the human self, that sickness came from the

mind and could be healed by right thinking. It was called New Thought, a

philosophy of the Gilded Age of Carnegie and Rockefeller, an age of extremes in

wealth just like the age Dean lived in. William James called this philosophy

“the Mind-cure movement.” It appealed deeply to Dean.

A Sort of a Song

Let the snake wait

under

his weed

and the writing

be of words, slow and quick, sharp

to strike, quiet to wait,

sleepless.

-- through metaphor to reconcile

the people and the stones.

Compose. (No ideas

but in things) Invent!

Saxifrage is my flower that splits

the rocks.

his weed

and the writing

be of words, slow and quick, sharp

to strike, quiet to wait,

sleepless.

-- through metaphor to reconcile

the people and the stones.

Compose. (No ideas

but in things) Invent!

Saxifrage is my flower that splits

the rocks.

William

Carlos Williams

No comments:

Post a Comment